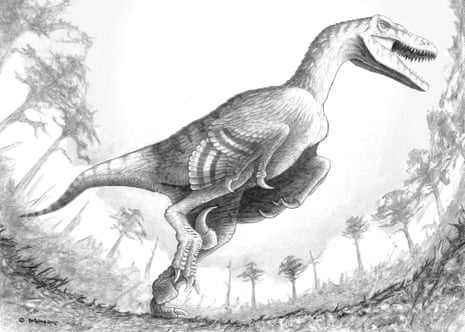

A dinosaur discovered in South Dakota had feathers on a raptor’s body, large claws and wings, according to a study published by the University of Kansas Paleontological Institute.

“It really was the Ferrari of competitors,” said Robert DePalma, head of the research team that discovered the fossils and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Palm Beach Museum of Natural History.

“It could run very fast, it could jump incredibly well, it was agile and it had essentially grappling hooks on the front and rear limbs. These claws could grab on to anything and just slice them to bits. It was utterly lethal.”

The Dakotaraptor was discovered in 2005 in the aptly named Hell Creek Formation, also known as the home of the famed Tyrannosaurus rex and the three-horned Triceratops.

Dakotaraptors were carnivores that walked the Earth about 66m years ago. They were about 17ft long, making them among the largest raptors in the world, and their wings stretched about 3ft. The only known raptor larger than the Dakotaraptor was the Utahraptor, which was 23ft long, but it died out approximately 60m years before the Dakotaraptor came along.

Scientists believe Dakotaraptors were feathered because of “quill knobs” found on the lower arm bones. These usually indicate where feathers attach to the bone. The discovery is the first time scientists have documented evidence that a large raptor had feathered wings, according to DePalma.

Despite having feathers and wings, however, the dinosaurs could not fly, because of their size. The purpose of their wings remains unclear but the study hypothesized that they could be for prey capture, protecting eggs or even mate attraction.

According to David Burnham, a study co-author and paleontologist, “the most scary thing” about Dakotaraptors was their sickle claw. It measures about 9.5in along the outer curve and is “bigger than anything” Burnham has seen in this category of dinosaur.

“It’s very laterally compressed so that means it was probably made for piercing flesh,” Burnham said. “It’s not a big, fat claw like on a T rex or something. It’s not just going to stomp you to death or bone-crush you to death. No, these things would slice and dice.”

It is not clear if the dinosaurs performed their gruesome hunting in groups, but Burnham said there was some evidence that they travelled in packs, as the discovery of their fossils usually yields more than one raptor in the same area.

The discovery proved that the terrifying animals used to live in South Dakota. They probably lived in other regions too. Now that scientists know what Dakotaraptor teeth and bones look like, discoveries from the past century can be classified. Teeth and bones found in Montana, Wyoming and North Dakota can be traced back to the Dakotaraptor, according to Burnham.

“They’ve been assigned to different animals not really knowing what they were,” he said. “Now we can be fairly confident they belong to this giant raptor.”

The discovery also filled a niche in the ecological system that scientists “thought was empty”. The Dakotaraptor fit into a predatory hierarchy as it was larger than some carnivorous creatures but smaller than the Tyrannosaurus. It was also built for running and could chase down prey other predators could not.

“Here you are throwing the most lethal animal you can possibly imagine into the paleoecology of that time period, so obviously it has dramatic effects on our interpretations of the paleoecology,” DePalma said.

Despite all of these discoveries, Burnham said there was more to learn. The researchers would like to “have a better idea of exactly how Dakotaraptors lived” but most importantly, they would love to find the still-missing skull.

“We found some loose teeth but we never found the skull,” he said. “It’s kind of the lottery prize for paleontologists if you get the head of the animal.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion